- Home

- Philip Freeman

Searching for Sappho Page 2

Searching for Sappho Read online

Page 2

1

CHILDHOOD

Don’t worry if the others return while I remain here in

Alexandria. . . . If you give birth to a living child. If it’s a boy,

let it live. If it’s a girl, leave it to die.

– LETTER FROM A MAN TO HIS WIFE (1ST CENTURY BC)

WE KNOW LESS about Sappho’s childhood than about any other part of her life. Because she rarely mentions her early years in her surviving poetry, we must rely on other ancient sources to imagine what life was like for a girl growing up on Lesbos in the seventh century BC. Many of these sources date from centuries later and from elsewhere in Greece, so they must be used with caution. Just because Athenian girls dressed as bears and worshipped Artemis in a coming-of-age festival doesn’t mean Sappho and her friends did as well. We can learn something of Sappho’s childhood from the hints she gives us in her poems and from the limited testimony about her early years in classical authors, but the best we can hope for is to create a tentative picture of her life as a girl by looking at the lives of other young women in ancient Greece.

The greatest challenge in the ancient world for children, especially girls, was survival. Disease, poverty, and a widespread preference for sons over daughters all took their toll. Infant mortality is notoriously difficult to establish in ancient times, but the best estimates are that one out of every four or even three children never saw their first birthday. There was no modern sanitation in the birthing room, and difficult deliveries were often a death sentence for both mother and child.

We know from Sappho’s poems that she came from a wealthy merchant family. A baby’s chances of living were undoubtedly better among such families, who could afford the best medical care, primitive though it was, and enough food for a nursing mother. But rich or poor, just as a woman weaned one child, another would be on its way. More often than not, a Greek woman from her midteens until well into her forties was pregnant.

Even if a child survived the trauma of birth, there was no guarantee the father would allow it to live. Classical stories are full of infants such as the newborn Oedipus or Romulus and Remus left to die in the empty countryside. But exposure was not just a literary motif. The Greeks called it ekthesis or “putting outside”—a pleasant euphemism for a most unpleasant act. Whether because of the inability of a family to feed a child, questionable paternity, birth defects, or other reasons, a father could choose to leave a child to die in the forest, on a dung heap, or in a place where it might be found by someone who would adopt it. In Sparta, the city elders examined all infants to decide those worthy to live, and those who failed the test were thrown into a pit on a nearby mountain.

To the ancient Greeks, exposure was not infanticide, since the child was not killed outright but had its fate placed in the hands of the gods. In this way of thinking the parents could avoid the bloodguilt that came with murder. Sometimes an exposed baby would be rescued by those who couldn’t have their own child or by slave merchants, but most infants were probably left unclaimed. Some cities, such as Thebes and Ephesus, outlawed the practice, while others tried to regulate it. Males were more valued than females for economic reasons in a world where parents relied on sons to provide labor and to care for them in their later years, so it’s likely that more girls were left to die than boys. The ancient Greek comedy writer Posidippus was undoubtedly exaggerating, but there must have been some truth in his grim humor: “If you have a son you raise him, even if you’re poor. If you have a daughter you expose her, even if you’re rich.” We have no idea how common the practice was on Lesbos, but it’s likely that on the day Sappho was born into a world of comfort and welcome, the cries of abandoned baby girls were fading into silence somewhere on the island.

MALE OR FEMALE, a child was not a member of its family until being accepted into the household during a formal ceremony. In Athens this was called the Amphidromia (“running around”) and took place a few days after the child’s birth. At this celebration the infant was given a name and carried at a trot around the family hearth, the sacred center of the home. Joyful feasting followed with a wide assortment of foods including, according to one ancient source, toasted cheese, boiled cabbages covered with olive oil, baked lamb, tenderized octopus tentacles, and many bowls of wine.

Soon after this, boys in Athens were publicly enrolled during their first year into their fathers’ phratries, or fraternal organizations, but the public rituals of baby girls in ancient Greece are less well known. One hint comes from a late classical text, which records that, in Athens at least, it was customary to place a tuft of wool—a symbol of her future role in weaving—on the door of a household with a newborn baby girl. Another clue comes from a recently discovered image in stone found in northern Greece at Echinos. On the relief is a carving of a woman presenting an infant girl to Artemis, a virgin goddess praised by Sappho who was honored by women for her help in childbirth and as a guardian of young girls. In front of the infant, at the center of the stone, is an animal ready for sacrifice. Behind the baby is a servant carrying fruit and cakes on her head. At the rear is a veiled woman, probably the mother, bearing a bowl of incense in thanksgiving to the goddess for a successful birth and as a prayer seeking a blessing for her new daughter.

SAPPHO’S MOTHER WAS Cleis, a name the poet would later give to her own daughter. Girls were usually named for a family member, often a parent’s mother, so Sappho may have taken her own name from her grandmother. We know little of the woman who bore Sappho, since Sappho mentions her mother only once in her surviving songs:

For my mother used to say

that when she was young it was

a great ornament if someone had her hair

bound in a purple headband.

Sappho never mentions her father. Later writers list no fewer than eight possible names for him, though the oldest and most common is Scamandronymos, a name with epic echoes, as it derives from the Scamander River that flowed past Troy. According to a late tradition found in the Roman poet Ovid, Sappho’s father died when she was only a child:

Six birthdays had passed for me when I gathered the bones of my father,

dead before his time, and let them drink my tears.

This may be nothing but a literary fiction, but Ovid had access to poems of Sappho now lost to us in which she may have written of losing her father as a child. If there is any truth to the story, Sappho grew up in a volatile and dangerous world without him.

Sappho never discusses any sisters in her poems, but ancient writers and the poet herself record that she had three brothers, named Erygius, Larichus, and Charaxus. The eldest may have been Erygius, but Larichus was apparently the youngest and Sappho’s favorite. He would later rise to the high position of cupbearer at the Mytilene town hall. Sappho would one day write scathing satires against her third brother, Charaxus, for sullying the family name with a prostitute in Egypt.

Sappho’s birthplace and home for most of her life was the beautiful island of Lesbos in the northern Aegean Sea. It lies just a few miles off the coast of Asia Minor (modern Turkey), which is clearly visible across the strait separating Lesbos from the mainland. The island itself is quite large but is divided now, as it was in antiquity, by two bays that reach deep into its interior. In Sappho’s day it was covered with pine forests and steep valleys with cultivated olive groves and apple trees. Even today it is a major flyway for birds migrating between Europe and Africa. Flowers grow everywhere on the warm and verdant island, while soaring mountains catch the cool afternoon breezes blowing from the north in the summer.

We know that Sappho was born on Lesbos, but where on the island is uncertain. The most likely place is Eresus, a small town on the southwestern coast now in ruins. But some claim she was from the opposite side of the island, at Mytilene, the major city of Lesbos in ancient times, as today. Sappho herself doesn’t say, but one likely possibility is that she was indeed born in Eresus and moved to Mytilene later, perhaps when she married.

The year

of Sappho’s birth is another thorny problem. Ancient writers say she lived at the same time as Alcaeus, another poet of Lesbos, and Pittacus, who ruled the island, as well as Alyattes, the king of nearby Lydia. All three of these men lived in the years just before and after 600 BC. We know that Sappho went into exile in Sicily sometime before 595 BC, so a reasonable guess is that she was born in the late seventh century BC and died some decades later.

Whatever the exact year of her birth, Sappho lived during a revolutionary period of Greek history. Sappho’s time was christened the “Archaic period” by modern historians who saw it as a precursor to the golden age of Greece in the fifth century BC, but the term is misleading. The long centuries of decline and struggle since the collapse of the mighty Bronze Age kingdoms of Greece had at last come to an end in the century before Sappho. Populations were exploding across the Aegean world, and trade was flourishing. Greek cities were establishing colonies on the coasts of the Black Sea, Africa, Italy, and even the distant shores of Gaul and Spain. Phoenician traders from the Near East were filling the markets of Greek cities with exotic goods and had brought with them an alphabet from which the Greeks forged their own writing system. The first philosophers and scientists in Western history, such as Thales of nearby Miletus, were beginning to speculate about the nature and origin of the universe.

And it was an age of poetry. In the previous century the bard Homer, traditionally thought to be from the island of Chios just to the south of Lesbos, had shaped the stories of Achilles and Odysseus into the Iliad and the Odyssey. His contemporary, the poet Hesiod, had composed songs about of the birth of the gods and how Zeus had devised the ultimate punishment for men: the beautiful Pandora, ancestor of all mortal women. And just a few years before Sappho’s birth, the poet Archilochus from the island of Paros had begun to sing of decidedly nonheroic themes, such as throwing away his shield and fleeing from a battle.

DAILY LIFE FOR a growing child in Sappho’s time in many ways wasn’t so different from life today. Boys and girls played with toys from infancy until they reached puberty, when they dedicated their playthings to the gods. For children who died before their time, the toys were often placed in their graves.

A child’s first toy was frequently a rattle made from brightly painted wood or terra-cotta in the shape of an animal such as a pig with small pellets of clay inside that made a loud noise when shaken. Bells and toy animals of all sorts were also popular, and many have been recovered by archaeologists. When the child was a little older, other toys and activities were available, such as balls, yo-yos, spinning tops, hoops, seesaws, swings, kites, rocking horses, and various games played with knucklebones. Boys were encouraged to play with toy carts and chariots, while girls dressed and cared for well-crafted dolls with movable limbs.

Children often had pets, as seen on Greek vases and relief sculptures. Small dogs were the most popular, but cats, birds, rabbits, mice, and grasshoppers also appear with children in art and literature. Wealthy families such as Sappho’s might even afford a monkey imported from Africa. Domestic farm animals were a popular object of entertainment. Anyte, another woman poet, who lived about 300 BC, records what must have been a common scene outside many Greek households:

The children put purple reins on you, Mr. Billy Goat,

and a bridle on your bearded throat.

Athenian grave stele of a young girl with doll and dog

(c. 340 BC).

(HARVARD ART MUSEUMS)

They teach you to race your cart around the temple of the god,

so he may watch them all having their fun.

Sappho must have also spent time as a child wandering the mountains and glades of Lesbos. Her poems are rich with references to flowers, birds, and the beauties of nature on her island. It’s hard not to see a memory of her own childhood in one surviving fragment of her poetry:

Evening, you gather together all that shining Dawn has scattered.

You bring back the sheep, you bring back the goat, you bring back

the child to its mother.

EDUCATION IN EARLY Greece was a mixture of both practical and theoretical knowledge. Boys trained their bodies with hunting, riding, and gymnastics and their minds with reading, writing, and arithmetic. Music, dancing, and especially poetry were an essential part of education, with boys memorizing large portions of the songs of Homer. The Iliad and the Odyssey were, as the ancients believed, the heart of what every boy needed to know about piety, courage, and loyalty. The words of the later Greek rhetorician Heraclitus could just as easily apply to Sappho’s day: “From his earliest years, the child beginning his education is given Homer as a nurse for his unformed mind. His poems are swaddling clothes and our minds feed on his milk. He is always there by our side as we grow up.”

For a typical Greek girl, however, education would have been much more limited. Learning how to properly manage a household (Greek oikos) was central to a young woman’s training. The word oikonomia or “running of the oikos” is, in fact, the root of our word “economics”—the modern economy being seen as a household on a grand scale. But although any female child would have learned all manner of practical skills, it’s doubtful she would have gained much beyond basic literacy, if that.

The Greek historian Xenophon wrote a handbook for household management in which he argued that mothers were the primary teachers of girls and instructed them in what they most needed to learn—namely, wool working and self-control. The carding and weaving of wool was essential for making clothing for a family and always fell to the women of the home. A girl who didn’t learn this vital skill was unlikely to find a husband. Many of the images of female children in the art of Sappho’s time depict girls sitting at the feet of their mothers as they work a loom. There were even wool-working contests in ancient Greece for girls with the greatest skill. Girls in the military-dominated city of Sparta—so often an exception—went far beyond these domestic skills to learn and practice athletic skills just as boys did, but only in preparation for giving birth to stronger sons.

As an aristocratic girl preparing to become a dutiful wife someday, Sappho would have learned all the domestic skills needed, but all we know for certain of Sappho’s education is what we can glean from her poetry. She never mentions weaving, aside from garlands of flowers. Instead, what has survived of her work shows a woman thoroughly trained in the Greek literary tradition with a consummate skill in the poetic arts. There are occasional references in later literature to female students in ancient Greek schools—Plato reportedly had two women in his famous Academy, one of whom liked to dress in men’s clothing—but there is no solid evidence of such formal institutions during Sappho’s day.

It was once fashionable to think of Sappho as the leader of a school for girls like one she herself had presumably been educated in, but there is no evidence for this in her poems. The most reasonable assumption is that either because of coming from an innovative family or because of her own uncompromising effort, Sappho learned the skills needed to perfect herself as a poet. Beyond a doubt, she possessed a remarkable natural talent. Perhaps she joined her brothers as their tutor lectured them in grammar, poetry, and music, or perhaps she was instructed privately by another poet, male or female, who recognized her genius at an early age. All that Sappho’s surviving poems tell us is that, as a girl, she learned the rich literary tradition of Greece, especially the poetry of Homer, very well and mastered the difficult techniques of composing various forms of Greek verse.

The musical patterns, or meters, of ancient verse were intricate, complex, and bound by rules that no poet could easily break. Unlike most modern songs, the poetry of the Greeks did not depend on rhyme or accent. What mattered were the number and pattern of long and short syllables within a line. One common unit was the flowing dactyl (long-short-short, or named for the one long and two short bones of the human finger. The stately spondee (long-long, or was more suitable for solemn songs. There were many possible combinations of patterns, such as Homer�

��s dactylic hexameters, with six dactyls as the basic form. But the most famous type of poetry composed by Sappho (later known as the Sapphic stanza) used shorter lines than Homer’s did, with little room for flexibility. To work within the constraints of ancient Greek meter required incredible skill in composition and word choice if a poet aspired to produce the fluid and seemingly effortless verse seen in Sappho.

We can be certain that Sappho also had training during her youth in instrumental music. Sappho is indeed best known for her lyric poetry—that is, poetry composed to be sung to the accompaniment of a lyre. One ancient Greek writer even claimed that Sappho herself invented a popular type of lyre called a pectis. A typical lyre was made from a tortoise shell with its hollow side covered by stretched animal skin to form a sound box. Two upright arms of wood or horn were fixed to this shell and joined above by a crossbar on which the strings were fixed over the face of the lyre and secured to a bar at its base. The strings, usually made from gut or sinew, numbered seven or eight and were tuned by being tightened at the crossbar. The strings were plucked with the fingers or with a small stick or quill called a plectrum, which Sappho also reportedly invented. Greek vases often show children like young Sappho sitting with a music master and learning the difficult art of playing the lyre.

IN HER SURVIVING poems, Sappho gives us only a few hints about the rest of her youth. In one fragment she addresses a girl still too young for marriage:

You seemed to me a small child without grace.

This may reflect Sappho’s feelings about herself during the awkward preteen years. In another papyrus fragment she looks back with longing on her girlhood days as she speaks to a friend:

. . . you will remember,

. . . for we in our youth

did these things,

many, beautiful things.

What these beautiful things are Sappho doesn’t say, but a rare, firsthand look into the life of girls before the age of marriage comes from another woman poet, Erinna, who lived three centuries after Sappho. In a moving and beautiful poem called The Distaff, she laments the death of her childhood friend Baucis and remembers when they were girls:

Searching for Sappho

Searching for Sappho Saint Brigid's Bones

Saint Brigid's Bones Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great Heroes of Olympus

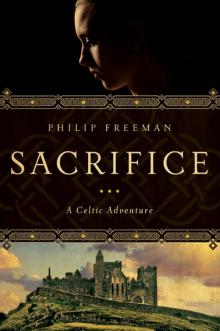

Heroes of Olympus Sacrifice

Sacrifice