- Home

- Philip Freeman

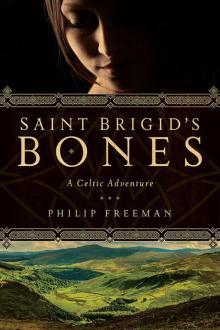

Saint Brigid's Bones

Saint Brigid's Bones Read online

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Author

For Alison

IRELAND

SAINT BRIGID’S BONES

Chapter One

I never meant to burn down the church.

That’s what I kept telling myself as I stood in front of Sister Anna’s hut.

It was a cool morning for mid October and dark clouds from the west threatened rain at any moment. Sister Anna was the abbess of the monastery of holy Brigid at Kildare. Her hut was a small structure made of rough-hewn grey stone with a thatch roof. When Brigid was alive she had cultivated a patch of bluebells and golden buttercups in front that made the place seem quite cheerful. But now the flowers were gone and nothing but a cold stone bench stood beside the wooden door.

I took a deep breath and knocked. I prayed that God would have mercy on my soul, for I knew Sister Anna would not.

“Come in.”

I pushed open the door and stooped to enter the hut, careful to close the door gently behind me. Sister Anna sat at her desk beneath the single window in back writing on a piece of parchment. She did not look up.

The abbess was a woman of about sixty with white hair and dark eyes. She wasn’t wearing her veil on her head at the moment, but this wasn’t unusual as we seldom did so unless we were at worship. Like all the sisters, her tunic was of undyed wool spun and woven into a simple cloth and tied around the waist with a leather belt. We looked quite similar to women of the druidic order except that their clothing was bleached white and each wore a small golden torque around her neck. Instead of a torque, we wore a plain wooden cross.

Sister Anna wrote with her left hand, which was understandable as her right arm hung uselessly at her side. The right side of her face was also deeply scarred, obviously from some accident years ago, but she never spoke of it and no one dared to ask. To say she was stern would have been an understatement, but I had a great deal of respect for her, as did the other sisters. I don’t believe I had ever seen her smile. She was a devout Christian woman and an able leader. Her style was different from that of Brigid, but in the decade since our founder had died she had held the monastery together and continued our mission against formidable odds.

“Sister Deirdre, come and stand before my desk where I can see you better.”

Even after her many years in Ireland, I could always hear a faint British accent in her voice. I moved into the hut and stood where she told me.

“Brother Fiach has told me what happened at the church at Sleaty, but I want to hear what you have to say. Tell me, but keep it brief, if that is possible for you.”

I cleared my throat and began.

“As you know, I left our monastery a few days ago with two of the sisters to finish preparations for the new church at Sleaty across the Barrow River. We arrived just as the tenant farmers from the monastery, who had been helping with the construction, were leaving to return here for the harvest. Brother Fiach had stayed to finish carving the stone cross in front of the church. He had used some of the stones from the old Roman trading post there. Of course, the last of the Roman merchants left years ago after—”

“I said brief, Sister Deirdre. I don’t need a history lesson.”

“Yes, I’m sorry. Well, Brother Fiach was putting the final touches on the cross when we arrived. He had finished the wooden altar the previous day as well as the beds in the back room for the sisters who would be staying there through the winter. I was impressed that everything had been made from solid oak, like our church here. The Sleaty church could hold at least thirty worshippers standing close together. Father Ailbe once told me that in one of the churches he visited in Rome, the wealthy parishioners actually sat on wooden pews, though I really can’t imagine why they—”

“Sister Deirdre!”

“Yes, brief, I’m sorry, Sister Anna. Well, I couldn’t sleep that night, even though I was exhausted, so after the others went to bed I went into the church and lit a candle on the altar. I knew that we didn’t have many candles left and it was a terrible waste, not to mention dangerous with all the sawdust still around, but I needed to pray and the light in the darkness helped. While I knelt there, I admired the linen cloth on the altar that had been embroidered by Brigid herself. It was bordered with intricate, interlaced patterns in green and gold along the edges, with fantastic, richly colored animals and angels dancing in the center. I thought it was a beautiful adornment for the new church. I was also thinking how proud Brigid would have been of the work we had done.”

I paused for a moment, thinking of how much I had loved looking at that cloth in our church at Kildare since I was a little girl. I knew many had attributed healing powers to it.

“Continue, Sister Deirdre.”

“Well, I prayed at the altar for a long time. I thought I heard something at one point and went outside to check, but there was no one there, so I went back inside. It must have been the flickering shadows on the walls that finally lulled me to sleep. The next thing I knew Brother Fiach was dragging me out the church door. I was coughing and choking and could barely see anything with all the smoke around me. I suddenly remembered the altar cloth of Brigid and started back into the church to get it, but Fiach pulled me away. I kicked him and screamed that I had to find the cloth, but thankfully he didn’t let go. I would have died if he hadn’t held me back. The two sisters were running with buckets to bring water from the well, even though it was clearly hopeless. The fire was devouring the freshly-cut oak and had turned the church into a raging inferno. There was nothing the four of us could do but fall on our knees as we watched the church burn. We huddled together all night beside the stone cross, warming ourselves on the embers of the dying fire with a single blanket wrapped around us. By morning there were only smoking ruins.”

For a long time Sister Anna simply looked at me without saying a word. I swallowed hard and braced myself for the storm I knew was coming. Then at last she spoke.

“Needless to say, I am most disappointed.”

“I’m so sorry, Sister Anna, I didn’t mean to—”

“Sister Deirdre, for once be quiet and listen to me.”

I nodded with my head bowed and allowed her to continue.

“I have sent a message to King Bran, who owns the lands at Sleaty, to let him know what happened and to ask that we might be allowed to begin again in the spring. I hold out little hope that he will grant this request. The agreement to lease his land specified that the church must be completed by the end of October. Bran is not a forgiving man, therefore we must consider the project at Sleaty effectively dead. There will be no mission in Munster and no support for the monastery from that source.”

I continued to stand silently.

“You’re an intelligent woman, so I won’t explain to you what that loss means for us. Do you see this abacus on my desk?”

I nodded that I did.

&n

bsp; “Let me just say that I have been calculating how long we can continue operating with our current supplies and projected harvest. If my figures are correct, we’ll begin running low on food this coming spring and will have to start turning the needy away, the first time we have done so in the fifty years since Brigid founded this monastery. Perhaps the donations from pilgrims at holy Brigid’s day in February will be large enough to see us through the summer, though I doubt it. I was counting on the harvest from the new church at Sleaty to supplement our stores beginning next autumn. Now there will be nothing.”

She stood up and walked from behind her desk to stand in front of me. She was a small woman, but her presence more than made up for her stature.

“Brother Fiach has taken full responsibility for what happened at Sleaty.”

I started to protest but she raised her hand.

“No, don’t speak. I’m not interested in assigning blame. I know how the fire began, but it’s too late to change that now. I am not going to punish you.”

I must have looked shocked.

“Oh, I know you’d like me to put you on bread and water until Easter or some such penance, but frankly, Sister Deirdre, I fail to see what good that would do. Instead, let me ask you a question and I expect an honest answer: Are you happy here at the monastery?”

I had never heard the abbess ask anyone if they were happy before.

“Yes, Sister Anna. I’ve spent most of my life here, when I wasn’t with my grandmother just down the road. I grew up with Brigid and the sisters and Father Ailbe. I know I only took vows three years ago, but this place is my home.”

“Somehow, I don’t think you’re being honest with me—or yourself. You grew up here, indeed, but you grew up in another world of druids and bards as well. I don’t doubt that you are trying to be a good Christian, but I’m not convinced you want to be a nun. I can’t help wondering if you came to us at a time of tragedy in your life because we were convenient.”

There was too much truth in what she said for me to deny it outright, but it was more complicated than she made it seem. At least I hoped so.

“It’s true, Sister Anna, that part of the reason I joined the monastery is because I’ve always been comfortable here. But my desire to be a sister of Brigid’s order and to serve God is sincere. I know I’m not like the rest of the sisters. I come from the Irish nobility. I was trained as a professional bard. My father was a great warrior, though a pagan. My grandmother is a druid seer. But my mother was a baptized Christian, as am I. Though, if I may ask, what does this have to do with the fire at Sleaty?”

“Nothing, perhaps. I’m not accusing you of burning down the church because you’re unhappy here. I’m simply wondering if the reason such a thing could happen is because you don’t have your mind on your work. Don’t forget, Sister Deirdre, I’ve known you since you were a little girl. You were always a joyful person with great focus on what you wanted to achieve in life. You’re the best student our school ever produced and, I know, one of the finest bards in Ireland. But since you took your vows I’ve seen little joy or purpose in you. I know what you lost. I am sympathetic. But you are like a ship adrift in a storm and I can no longer wait for you to find safe harbor.”

Sister Anna walked over to gaze out the window, then turned back to me.

“I’m not ordering you to leave these walls. But as your abbess, I am requiring that you prayerfully consider what it is you are searching for here. This place is a refuge of sorts for all of us—there’s no shame in that. It will be a haven for those in need as long as it exists, which may not be much longer. But the primary mission of our order is to serve God by serving others. We are not a guest house for lost souls, Sister Deirdre. If your focus is not on our Lord and ministering to the needy of this land, then there is no place for you here.”

I didn’t know what to say. I simply stood there looking down at the dirt floor.

Suddenly, there was a shout outside the hut and Garwen burst through the door without even knocking.

“Sister Anna! They’re gone! They’re gone!”

Sister Anna had always insisted on protocol. For someone to rush into her hut uninvited was behavior that would have earned even a child a good lashing.

“Sister Garwen, what is the meaning of this? How dare you enter here without my leave. Get out this instant! I’ll see you in the church later to discuss your punishment.”

“But Sister Anna, I’ve just come from the church and they’re gone! I was there to clean and polish them just like you told me to. I brought wine to wash them and a new woolen cloth to wrap them in, but they’re gone!”

“What on earth are you talking about, child? What is gone?”

“The bones!” Garwen sank to her knees as she spoke. “The bones of holy Brigid—they’re gone!”

Chapter Two

The first few hours after the discovery of the missing bones were chaotic. Everyone was in shock. Sister Anna immediately told Garwen to send the brothers to the gates of the monastery to stop anyone trying to leave. The abbess then rushed to the church with me two steps behind. I suppose I thought I could be of some help, but mostly I had to see the empty chest for myself.

Sister Anna pushed through the ill-fitting door on the sisters’ side of the church and went to the altar in front. It was a simple wooden table with a golden crucifix on top. The silver paten for the Eucharist sat next to it, but both were untouched. On the right side of the altar was a stone slab marking the tomb beneath of Conláed, our first bishop, who had died many years before. On the left side was the small oaken chest holding Brigid’s bones. There had never been a lock on it, only an iron latch tied with a crimson ribbon that once belonged to Brigid herself. The lid was wide open, as Garwen had left it. The small jug of wine for cleaning the bones, a few old rags, and the new woolen cloth all lay beside the chest where Garwen had dropped them before rushing out. The spilled wine had spread across the stone paving of the floor and was already soaking through the joints into the ground beneath it.

“Dear God in heaven,” whispered Sister Anna as she peered into the blackness of the chest.

She knelt and touched the rough wooden bottom. The bones were always kept tightly bound in a leather sack, which was also missing. Sister Anna rested her head against the edge of the chest and closed her eyes, whether in prayer or anguish I couldn’t tell. I knelt beside her and worked up the nerve to place my hand on her shoulder in comfort. I felt her stiffen at once. She rose quickly and stared at me with hard eyes. If she had seemed on the verge of tears a moment ago, it had quickly passed.

“Sister Deirdre,” she said sharply, “go and bring Sister Garwen back immediately.”

I ran out of the church and found Garwen weeping on the bench in front of our scriptorium. She was in such distress that I practically had to carry her back to Sister Anna.

“Sister Garwen,” abbess said when we had returned, “did you touch anything after opening the chest? Anything at all?”

“No—no—Sister Anna—I swear—nothing,” Garwen managed between sobs. I thought she was about to collapse.

Sister Anna grabbed her by the shoulders and shook her.

“Look at me, you fool of a girl. There isn’t time for this now! Was there any sign that someone had been in the chest before you? Was the ribbon untied? Was the latch open? Did you see anyone leaving the church?”

“No, no—Sister Anna—I—didn’t see or hear—anyone. The church was—empty when I arrived. The latch—was closed and tied—just like it—always is.”

Sister Anna turned away and swore under her breath, something I had never heard her do before.

“Garwen,” I said, as I took her hand and held it gently. “Please, try to remember something for me. Was there any dust on the latch when you opened it?”

The question surprised her and she seemed to calm down as she considered it. Sister Anna turned back suddenly and looked first at me, then Garwen.

“Dust? Well, yes, Deirdre, the

re was.”

“Are you sure? Absolutely sure?” the abbess asked.

“Yes, Sister Anna, I’m positive. I remember kneeling in front of the chest to untie the ribbon and noticing how much dust had collected on the latch. I was embarrassed that it was so dirty. I untied the ribbon, then dipped one of the rags in the wine and wiped the latch clean before opening the chest.”

“Mudebroth!” said Sister Anna, which I took to be a British curse word. I didn’t ask her what it meant.

“Sister Garwen, go and tell the sisters to search all the buildings. Look everywhere. Send someone back here immediately if you find anything unusual, anything at all.”

“Yes, Sister Anna.” Garwen bowed and left the church.

The abbess and I were alone in the church once again.

“Sister Deirdre, you realize of course this makes matters much worse. If there was dust on the latch, it could have been weeks since the chest was opened and the bones stolen. The last time the bones were cleaned was early August. They could be anywhere on the island by now.”

“Yes, Sister Anna.”

The abbess began to search around the altar. I knelt by the chest again and looked inside. It was as empty as a tomb.

“Close the chest, Sister Deirdre. It will be too painful for everyone to see it empty.”

“Yes, Sister Anna.”

I pulled the heavy lid over on its hinges and brought it down gently. It made a lonely, hollow sound as I shut it and fixed the latch. I started to tie the ribbon when I noticed something strange.

“Sister Anna, look at this. It’s different!”

The abbess knelt by the front of the chest and looked at the latch.

“It seems the same latch to me, Sister Deirdre. What are you talking about?”

“No, Sister Anna, not the latch, the ribbon. We’ve always used Brigid’s ribbon of fine red linen to tie the latch shut. But feel this.”

She took the ribbon from my hands and ran her fingers along it.

“Sister Anna, it looks exactly like the ribbon we’ve always used. Even by touch most people couldn’t tell the difference, but this isn’t linen, it’s—“

Searching for Sappho

Searching for Sappho Saint Brigid's Bones

Saint Brigid's Bones Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great Heroes of Olympus

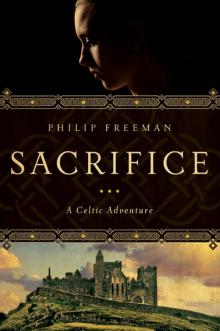

Heroes of Olympus Sacrifice

Sacrifice