- Home

- Philip Freeman

Oh My Gods Page 2

Oh My Gods Read online

Page 2

By 500 B.C., the Greeks had colonized the Mediterranean and Black seas from the Crimea to Spain. Wherever they went they would establish a polis, a city-state—the root of our word “politics.” Many cities abroad and in the Greek homeland were ruled by popular tyrants who lavished state funds on the arts and public theater. In Athens, the family of the tyrant Pisistratus encouraged, among other celebrations, a springtime festival to the god Dionysus in which choruses and actors performed tragedies and comedies. The festivals continued and grew even after the tyranny was overthrown and replaced by Athenian democracy to usher in the celebrated Golden Age of Greece. Many of these productions, such as Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, are major sources for Greek mythology. Aside from plays, contemporary writers of the period, such as the lyric poet Pindar and the historian Herodotus, record many enduring myths.

The defeat of Athens by Sparta in the Peloponnesian War at the end of the fifth century B.C. brought an end to the great artistic flowering of the Golden Age, but stories and myths continued to be as popular as ever. The conquests of Alexander the Great less than a century later spread Greek culture to Asia and Africa, especially to the newly founded city of Alexandria in Egypt. There and elsewhere around the Mediterranean, scholars collected and edited centuries of Greek mythology on papyrus scrolls.

Far to the west, a small village on the banks of the Tiber River in central Italy had begun to expand beyond its seven hills. The Romans had inherited a rich mythological tradition from their own ancestors, but they added many other stories when they encountered the cultured Etruscans and Greeks. Native Roman gods were ephemeral deities of field, hearth, and home. While their rituals were faithfully observed, many of the stories behind them were lost. The ancient myths that survived were often disguised as early history, such as the tale of Romulus and Remus. These Roman stories may surprise modern readers in tone and purpose compared with Greek mythology. To a Roman, unwavering loyalty to the state was the greatest virtue, so that many early myths read like stark political propaganda.

The Romans were always ambivalent about the Greeks, admiring their sophisticated culture but dismissing their neighbors to the east as inferior in honor and the manly art of war. However, as their power spread across the Mediterranean and republic grew to empire, the Romans sought to tie their own history to that of the Greeks by claiming an origin from the Trojans. Thus while distancing themselves from the Greeks in lineage, they nevertheless wrote themselves into the greatest of Greek stories—surprisingly as the heirs of the losers. The Latin poet Virgil crystallized this tradition in his monumental poem the Aeneid. In this epic the Trojan refugee Aeneas and his band of hearty followers venture ever westward through countless toils and snares eventually to become the ancestors of the Romans.

Throughout imperial times, both Romans and the Greeks under their dominion continued to retell the ancient myths, often with additions both subtle and bold. The Greek biographer Plutarch preserves many traditional stories in his prolific works, while his countryman Pausanias includes a number of myths in his travelogue of sites he visited throughout Greece. But the greatest of these writers was the Roman poet Ovid, who preserved many Greek myths that would otherwise have been lost forever. His Metamorphoses is an epic of mythological tales built around the theme of supernatural changes. Read widely long into medieval and Renaissance times, it became the most influential source of mythology in later art and literature.

There are many ways to write a book on classical mythology, all of which have their strengths and weaknesses. Many contemporary authors choose to explore the myths from a particular thematic angle, such as a function of religious ritual, a reflection of social structure, or an expression of the universal unconscious. These approaches and many more, such as feminist criticism, can be productive ways to look at classical myth, but my goal in this volume is more modest. I simply want to retell the great myths of Greece and Rome for modern readers while remaining as faithful as possible to the original sources. Sometimes this means paraphrasing a single ancient author, while in other cases I merge a number of different classical sources. In some stories I draw on authors centuries apart to create a complete version of a tale. Such an approach is unavoidable as few myths are wholly preserved in just one writer. Often I have had to choose which version of a story or episode within a myth to present as there are usually variants, some of which contradict each other. I describe the ancient authors I use for each tale in the notes at the back of the book. Readers interested in learning more about a particular story are encouraged to read the appropriate primary sources.

For Greek names, I have tried to use the spelling most familiar to contemporary readers rather than a strict transliteration of the Greek. Thus Hercules instead of Herakles, and Oedipus for Oidipous. With less familiar names I have tried to pick the form I think is most pleasing to the modern eye and tongue. Different forms, along with their Roman equivalents, are listed under each name in the Glossary.

No one should be allowed to have as much fun writing a book as I did while putting together this collection of myths. I have so enjoyed teaching these stories to my students for years that the opportunity to present them to a wider public was irresistible. My heartfelt thanks go out to all who helped me in this endeavor, including the National Endowment for the Humanities and the libraries of Harvard University. But as always, my greatest thanks go to my students, who have so patiently listened to me tell these myths in my classes. Whatever you do in life, may you never lose your love for old stories.

CREATION

In the beginning there was Chaos—a great, bottomless chasm beneath the endless darkness of the cosmos. Out of Chaos came the broad green Earth, unmoving seat of the gods, and the black hole of Tartarus below. Then from Chaos sprung Eros, who overcomes the minds of gods and mortals alike with burning desire. Out of Chaos also flew dark Erebus, the Underworld, and his sister, black Night. Erebus made love to Night and fathered the lofty air called Aether and bright Day.

Earth gave birth to starry Sky, equal to herself, who covered her on every side and became her mate. From Earth came the high mountains and the swelling sea. Then Sky made love with Earth and their children were the gods Coeus, Crius, and shining Hyperion, along with deep Ocean that surrounds the Earth, then Iapetus, Theia, Rhea, and Themis, who brings order to the world. Earth also bore Sky a goddess, Mnemosyne, who never forgets, and golden-crowned Phoebe, as well as lovely Tethys, goddess of the sea. Last of all was born Cronus, youngest of the shining gods, the most willful and crafty of all Earth’s children.

The broad Earth bore other creatures, such as the single-eyed Cyclopes, who delight in violence and brute force. These were Brontes of thunder, Steropes of lightning, and Arges, bearer of light. She also bore terrible Cottus, Briareus, and Gyges, huge monsters of enormous strength with a hundred arms springing from their shoulders and fifty heads each.

Father Sky hated all his children. As soon as they came from the womb, he gleefully shoved them into a hole in the ground and would not let them see the light of day. Mother Earth groaned from the pain of her children inside her and hatched a plan for revenge. She crafted a giant sickle from the hardest adamant and showed it to her offspring.

“Dear children of mine,” she pleaded, “who will avenge this evil done to you and me by your wicked father? Who will dare to strike back against the power of Sky?”

None of those hiding in her belly said a word, as they were all deathly afraid of their father. Only the youngest of the gods, the clever Cronus, spoke up: “Mother, I will do it. I’m not afraid of Sky, especially since he wronged us first!”

The Earth was thrilled at the courage of her son and gave him the sickle with its jagged teeth. When night was drawing near, Sky at last stretched himself out on the Earth, eager to make love to her. At just the moment they were about to join, Cronus sprang from his hiding place and grabbed his father’s genitals with his outstretched hand. With a single swing of the blade, he castrated Sky and threw what he had

reaped behind him. Blood splattered everywhere across the face of the Earth. Where it hit the ground, vengeful Furies sprang forth as well as wicked giants decked in shining armor, brandishing great spears. Nymphs also arose from the bloody mud.

The severed testicles of Sky sailed through the air and landed in the sea, where they floated at last to the island of Cyprus. There the pounding waves stirred up a white foam on the beach. Inside the foam the goddess Aphrodite was born, immortal divinity of smiles and sweet delights who urges all to lose themselves in passion.

Now it was Sky who groaned at the pain within him. He called his children Titans and cursed them as ungrateful whelps who had wounded the very father who had given them life. And he swore that in time Cronus would pay dearly for his wicked deed.

The family of Chaos bore untold sons and daughters, some children of beauty and hope but most of darkness and despair. The goddess Night gave birth to hateful Doom, Blame, Distress, Nemesis, Deceit, Strife, Old Age, and Death itself. She also bore Sleep and the tribe of Dreams, for good and ill, and the three Fates who weave our destinies. From her womb also sprang pitiless Furies who hunt down gods and men to seek vengeance. Night’s daughter Strife bore Toil, Neglect, Hunger, and Pain, along with War, Murder, Lies, and many other woes. But Sea gave birth to kindly Nereus, who in turn mated with a daughter of Ocean to father fifty nymphs of the wind and waves.

Many other children were born of these early unions, such as Medusa and the Gorgons, along with Echidna, half beautiful nymph with fair cheeks and golden hair and half monstrous serpent. Typhon, mighty son of Tartarus and Earth, lay with Echidna and fathered Orthus, the dog, as well as the monster Geryon and the three-headed hound Cerberus, who guards the door to the Underworld so that no one may ever leave. Echidna also gave birth to Chimaera, a beast who was a lion in front, a goat in the middle, and a dragon in back. Chimaera was raped by her brother Orthus and bore the riddling Sphinx. Tethys, daughter of Sky and Earth, gave birth to all the great rivers of the world and to thousands of nymphs who live in streams and ponds. The daughter of Ocean, Styx, by whom the gods swear, bore Aspiration, Victory, Power, and Strength. Phoebe came to the bed of her brother Coeus and became pregnant with gentle Leto and her sister Asteria, who was the mother of honored Hecate. Theia, sister of Tethys, slept with her brother Hyperion and gave birth to Helios the sun, Selene the moon, and Eos, goddess of dawn. Eos in turn gave birth to the winds and the morning star. Iapetus, son of Sky and Earth, went to the bed of the nymph Clymene and she bore him four sons. These were stern Atlas, proud Menoetius, forward-thinking Prometheus, and foolish Epimetheus. Countless other divinities were conceived in those days, so that no one could number them all, until the world itself was full of gods.

Now that Cronus had defeated his father the Sky, the young Titan ruled all of heaven and earth. He overcame the resistance of his sister, Rhea, and lay with her, fathering six splendid children. There was Hestia, goddess of the hearth, then Demeter, who brings the fruits of the ground to ripeness, and Hera of the golden sandals. Rhea also gave birth to mighty, merciless Hades and Poseidon, shaker of the earth. But Cronus was a jealous god who had learned from his parents that he was destined to be defeated by his own child and lose his power. Thus when each child was born, he snatched it from weeping Rhea and swallowed it whole.

Rhea suffered such grief from having her children eaten that she went to her father and mother to ask how she might have vengeance on crooked-scheming Cronus. They felt pity for her and told her all that they had revealed to Cronus, how he would one day lose his throne to a son yet unborn. Then they told her to go to the island of Crete to bear the child now in her womb. Alone in a cave high on a mountain, she gave birth to Zeus. Her mother, the green Earth, came to her there and took her grandson away to hide in a secret place. But ever-vigilant Cronus was close on the heels of his wife and soon arrived in Crete to demand the newborn child. Earth, however, had given Rhea a great stone wrapped in swaddling clothes that she handed to Cronus in place of her baby boy. Greedy Cronus snatched the bundle and shoved it down his throat, never suspecting that he had been deceived.

As the years passed, Earth raised Zeus on Crete hidden from the eyes of his father. The boy soon grew wise and strong, until one day he emerged from his hiding place. He hatched a plot with the wise goddess Metis. She went to the unsuspecting Cronus and offered him a potion for his health, but it racked his stomach with pain and caused him to vomit up his deathless children. The offspring of Cronus then banded together with Zeus as their leader and challenged their father in the greatest battle the world had ever seen or will ever see.

For ten long years the younger generation of gods battled their elders, with neither side able to gain victory. It seemed as if Zeus would never be able to defeat his father, but then his grandmother Earth came to him with wise advice. Long before the birth of Zeus, his grandfather the Sky had imprisoned the Cyclopes in Tartarus along with the hundred-armed monsters Cottus, Briareus, and Gyges. Cronus and the other Titans, fearful of their power, left them there to live in misery. Now Earth told her grandson that with the help of the Cyclopes and these three monsters, he might be able to overcome his father. Zeus then sped to Tartarus and freed them, bringing them back to Mount Olympus. He fed them nectar and deathless ambrosia to nourish their bodies and spirits. Then he spoke to them: “Children of Sky and Earth, listen to me. For ten years we have been fighting the Titans for control of the world, but neither side can gain an advantage. I call on you now to help us, to remember who it was who freed you from your bonds in the misty darkness of Tartarus.”

Cottus spoke for them all and answered: “Son of Cronus, we know that you are wiser than your father and his generation. You have freed us from our prison and we will not forget it. Come, we will fight with you and crush the Titans into dust.”

With that the Cyclopes forged lightning bolts for Zeus to serve him in battle and joined with the young Olympians in war. They marched on the Titans and fought until the sky roared, the sea rolled, and the earth quaked. The noise of combat was terrible and filled the earth. Zeus now raged with all his might and threw lightning bolts down on his enemies from the sky. The forests of the world burst into flame and smoke rose to the heavens. At last the tide of battle turned and the young gods began to drive back Cronus and his allies. The Titans turned to run, but were captured and cast down themselves into gloomy Tartarus. There they are guarded by the Cyclopes and will never again see the light of day, save for Atlas, son of Iapetus, who Zeus punished by forcing him to bear the weight of the heavens on his shoulders.

But just when Zeus thought the struggle was over, a new threat emerged. Typhon, son of Tartarus, rose against the young gods. Some say his mother was Earth herself or even Hera, but whatever his origin, he was a grave threat to Zeus. A horrible creature of hideous strength, he had a hundred snake heads with burning eyes. He bellowed like a bull and roared like a lion as he rushed Mount Olympus and began to climb. The immortals shook in fear and panicked. Typhon would have destroyed the gods that day if Zeus had not taken his weapons of thunder and lightning down to face him. He leapt from the mountain and struck the monster again and again with terrible blows. At last Zeus picked up the broken body of the creature and cast him down into Tartarus to dwell forever with the Titans, where Typhon rages still, bellowing typhoons across the seas.

Zeus now lorded over the immortals from the shining heights of Mount Olympus, ever watchful lest he himself should be overthrown as were his father and grandfather before him. He took the stone Cronus had swallowed in his place and set it up at the holy vale of Delphi as a monument to himself for ages to come. He chose this site because when he had released two eagles from opposite ends of the world, they met here beneath Mount Parnassus, marking the navel or center of the earth.

Zeus was the most powerful of the gods, but he knew he could not rule alone. He cast lots with his brothers Poseidon and Hades to divide the world among them. The sea fell to Poseidon and the underworld to Ha

des, while Zeus received the sky. The earth and Mount Olympus belonged to the three brothers alike, but all the gods knew that Zeus was their king.

The master of the gods decided he should marry and chose as his first wife Metis, who had forced Cronus to vomit up his brothers and sisters. He did this not out of love but cunning, for Earth and Sky had revealed to him that any son Metis bore to him would surpass him in power. Therefore when Metis was pregnant, Zeus swallowed her whole, just as Cronus had done to his children. He thought he had seen the last of his bride and her child, but soon he began to have a terrible headache. He ordered Prometheus, a nephew of Cronus who had taken his side against the Titans, to split open his head with an ax to relieve the pain—and out came the goddess Athena, wisest of the children of Zeus. Metis, however, remained trapped inside Zeus, where she was a constant source of good advice.

Searching for Sappho

Searching for Sappho Saint Brigid's Bones

Saint Brigid's Bones Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great Heroes of Olympus

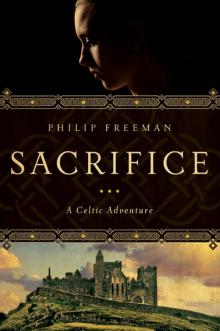

Heroes of Olympus Sacrifice

Sacrifice